A complex financial “phenomenon” that used to concern only those who were prone to chatting about things like the Federal Reserve and the yield curve at dinner parties, has seeped its way into the limelight with the public. By the title, you have likely guessed this “phenomenon” is inflation.

Inflation is abstract, confusing, complex, and unequivocally frustrating for everyone affected by it. Deemed the silent tax through which governments rob the purchasing power of its citizens, inflation pervasively degrades the value of our hard-earned money. While it is not always the government’s intention, there is not a doubt that inflation eats purchasing power. $1 today is worth more than $1 next year and far more than in 10 years.

To fully wrap our heads around the current inflationary environment which we have not experienced in the United States for over 4 decades, I began pondering how and why inflation occurs. Is it truly just a “monetary phenomenon” as the late and famous economist Milton Friedman coined it? Will it work itself out and eventually fizzle into nothing on its own?

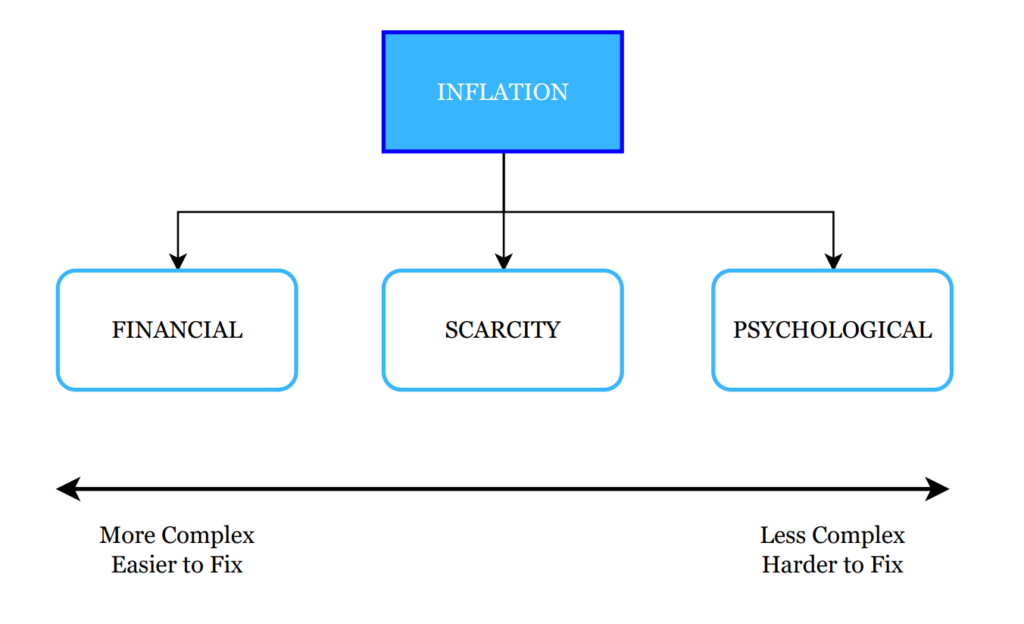

Ultimately, the answer to that is a resounding NO! In my experience and research, there are three major components, or pillars as we will call them, that act as the foundation for any inflationary environment (Figure 1). They are Financial Inflation, Scarcity Inflation, and Psychological Inflation. These can be characterized into ranges of “more complex, but easier to fix” and “less complex, but harder to fix”. Let’s dive in.

Financial Inflation (FI)

FI is undoubtedly the most complicated inflation to understand. It is generally “controlled” by monetary policy set by the Federal Reserve and fiscal spending by the US Government. The overall impact of the Federal Reserve actively purchasing treasury, mortgage-backed, and corporate bonds in the open market is effectively impossible to quantify, regardless of what any financial guru or pundit claims. The same goes for fiscal spending; there are second-, third-, and fourth-order effects that seem obvious in hindsight but were indeterminate when planning and initiating the spending.

The nature of the complexity is fortunately offset by the ease at which these inflationary pillars can be crumbled, if you will. All the Federal Reserve needs to do is stop purchasing bonds and/or raise interest rates. All the US government needs to do is reduce spending. While the actual decision to change monetary or fiscal policy is not as simple as taking a wrecking ball to a pillar of stone, in truth, impacting this type of inflation is simple.

If the Federal Reserve and the US government want to kill FI tomorrow, all they would have to do is unwind their bond portfolio immediately, raise rates to 15%, cut government spending to $0, and raise taxes 50% across the board. Is that ever going to happen? No, but you get the point.

Scarcity Inflation (SI)

SI is somewhere in the middle in terms of complexity and ability to fix. This is when prices of goods and services increase due predominantly to a shortage of supply. This materializes in many ways:

- The cost of new and used vehicles increasing dramatically due to semiconductor and computer chip shortages

- Increased energy prices due to a general lack of supply in oil and other forms of energy

- Higher cost of food due to an increase in the cost of inputs such as fertilizer, transportation and – energy!

Supply chains, manufacturing processes, etc. are complex and can be difficult to understand, but generally their impact on inflation is relatively easy to quantify. If a major oil refinery abruptly needs to go offline for an extended period, the price of oil is likely to increase because the capacity to produce finished, usable energy products (i.e., gas for your car) has suddenly decreased – thus scarcity.

We can also define any increases in costs of production due to deglobalization as SI. For example, the US has pervasively shipped broad spectrums of goods manufacturing overseas in the last 40 years to capitalize on far cheaper labor (globalization). Trends in the last 2+ years have tended towards deglobalization which means we will have to re-shore that manufacturing. This will inevitably lead to higher manufacturing costs. The supply of products produced overseas have become more unreliable (again, think computer chip shortages), so to bridge this gap between supply and demand, higher costs are unfortunately required.

Given the scenarios we have highlighted, it becomes clear that SI is harder to fix than FI. Combatting issues of scarcity – leading to higher prices – is not as simple as changing a few policies. It requires time, and a concerted effort from many participants across various industries.

Psychological Inflation (PI)

PI is simple and can come in several forms:

- If prices are going to be higher tomorrow, I need to purchase whatever I need today

- Prices are persistently going up, so I need my employer to provide cost of living adjustments

- The items I once bought are more expensive, so I’m going to reduce my discretionary spending and only purchase things I need

Easy to understand and not complex. It’s the public’s belief that prices in the future will be higher than they are today. Unfortunately, this simplicity comes with a serious downside, the difficulty in fixing it. PI is pervasive, elusive, and immensely sticky. Regardless of what the powers that be declare on TV or social media, once these expectations seep into the mentality of the general consumer, it’s difficult to convince them otherwise. “Mr. Biden, Mr. Powell, I know you say you want to fight inflation, but prices at my grocery store keep going up and my bills are getting more expensive.”

The reason PI is so difficult to fix is because the moment it becomes reality it signals a dramatic change in consumer habits. It’s the real-life application of “one in the hand is worth two in the bush”. Goods, services, and generally everything becomes infinitely more valuable NOW than it does THEN, both from a financial and psychological perspective. This can drive consumer demand to hoard staples (think toilet paper, toothpaste, food, etc.) causing shortages, compounding the issue.

To fix PI a recession is required. Demand needs to collapse, and prices need to come down to signal to consumers that inflation is not a mainstay. Until a material recession occurs, consumer habits are unlikely to change and perceptions on inflation will remain entrenched.

When analyzing and discussing these pillars, it becomes obvious that they are not independent. They are interconnected and dependent on one another in more ways than can be described. For example, PI changes consumer habits which can lead to hoarding, which can immediately impact SI in the form of shortages, as described above. FI can lead the Federal Reserve and US government to change the direction of their policies which could increase the working cost of capital for manufacturing companies, making goods more expensive, thus compounding the issues in SI.

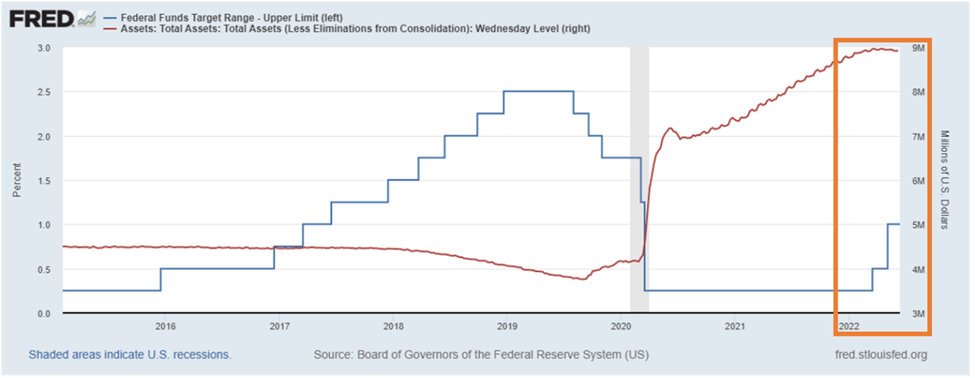

The way in which these pillars can impact one another is effectively infinite, however, each one contributes to inflation in its own way. In 2020 and 2021, the Federal Reserve and US government conducted massive stimulus programs which artificially inflated the economy and produced a dramatic misallocation of resources. This resulted in tangible and immediate FI (see the price of Bitcoin and the housing market over that timeframe). Currently, the Federal Reserve is in the process of reducing its bond holdings and raising interest rates (Figure 2). Generally, this leads to a reduction in FI.

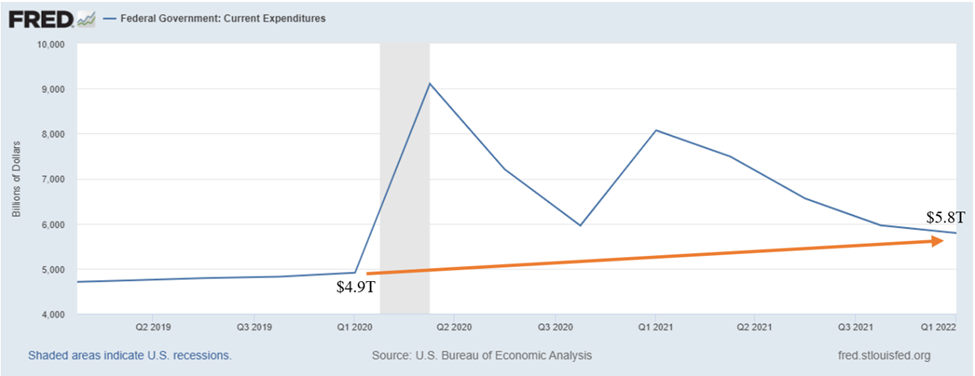

However, despite the claims of the current administration, the US government has not reduced spending to pre-2020 levels (Figure 3). While there are many reasons expenditures are higher, simple things that contribute to FI are continued moratoriums on student loans and proposals for partial or full student loan debt cancellations. This means that while the Federal Reserve is attempting to “fix” their contribution to FI, any attempts are effectively offset by the higher and continuous US government spending. Therefore, we can conclude that the impacts from FI are currently neutral. Until the government materially reduces spending or the pace at which the Federal Reserve is attempting to reduce FI exceeds said spending, this “neutral” condition will persist.

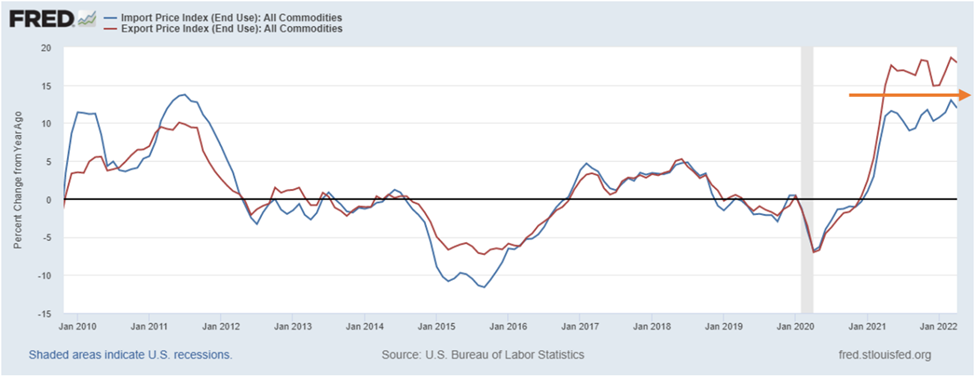

The SI environment has remained elevated over the same time frame but has unfortunately persisted through 2022. This has come in the form of much higher prices across most commodities, along with shortages of essential products produced both overseas and domestically. An easy way to see this is via the index of Import and Export Prices which shows the dramatic increase in the cost of goods that are both entering and exiting the country (Figure 4). While SI is far more diverse than just imports and exports, I believe this accurately encapsulates the current SI environment, broadly. Increases in prices have stopped going up – that is their rate of change has plateaued. Maintaining year-over-year (YoY) price increases of >10% is not necessarily *good* but it’s better than the trend continuing higher to result in 20% or 30% YoY increases.

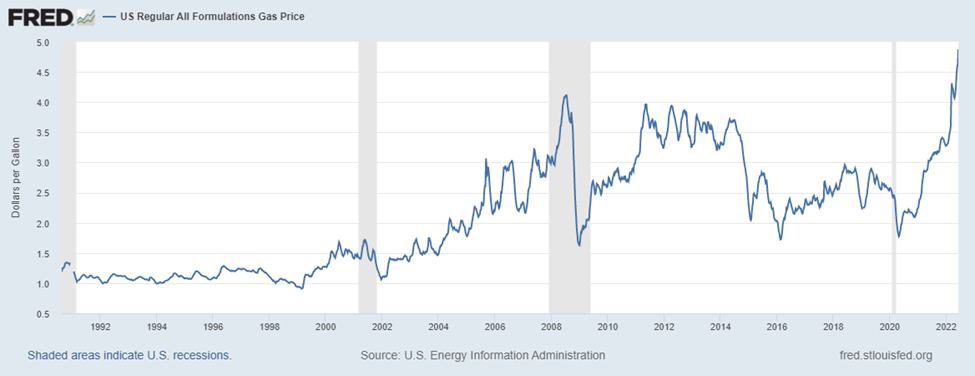

The exception is energy, which is a critical component of SI. The best way to depict the immediate impact the continued increase in energy costs has on consumers is via the domestic average price of gasoline (Figure 5). This chart is rather jarring considering the price of gas has now reached an all-time high and has increased by over $3/gallon in less than 2 years. While beyond the scope of this article, I believe these circumstances are unlikely to change anytime soon and will persist into the foreseeable future.

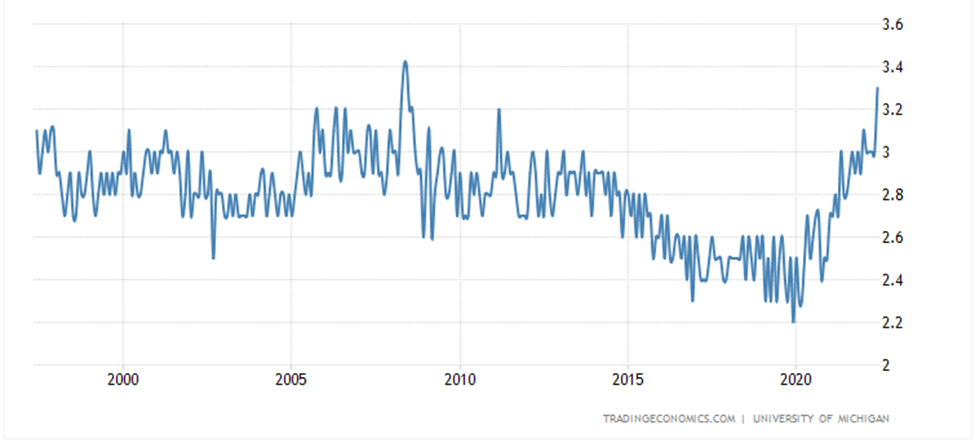

PI has slowly but surely creeped into the mindset of US consumers. While we are not at a place of concern yet, the initial signs of stickiness are beginning to show. The University of Michigan puts together excellent sentiment surveys; one of these surveys analyzes the 5-year inflation expectations of general consumers (Figure 6). This has reached 13-year highs at 3.3% and is just a hair away from making new highs since 1992.

This survey tends to lag current inflation rates and is rather slow-moving, so the current persistent uptrend is concerning. If we do not have a materially decline in prices or have a recession soon, I would not be surprised to see the results of this survey, which are published monthly, begin to spike even higher.

Overall, we can conclude a few things from the three pillars. First, FI is not declining as much as the financial media, Federal Reserve, or US government would lead us to believe. If anything, FI is currently in a more neutral state. Second, SI has tapered off as it relates to price increases, but this is only for goods and services inflation. Energy costs have yet to top out and continue to persist higher on a YoY basis. We can conclude this produces an upward pressure in prices from SI. Third, PI has not become problematic – yet. As we’ve reiterated multiple times, it is inherently sticky. The slow and steady pace that inflation has worked its way into the minds of consumers is concerning to say the least.

I can confidently say that people I talk to – who in the past have generally not concerned themselves with financial markets or inflation – are increasingly asking me about it and wondering about its current and future impacts. In my opinion, this is a key sign that FI and SI have slowly begun to impact PI. A simple way to think about this change in behavior is that some families will now give more thought to a summer vacation (and possibly not take one) when in the past it was a given. The shift happening under the pillar of PI is not being offset by the actions taken to address FI and SI.

Even so, if the Federal Reserve is successful in reducing FI, this would almost definitively cause a recession. Manufacturing a recession in the face of rising costs on things such as cost of living, consumer staples, and even some discretionary goods, is a losing gambit. In the event of a recession, this would likely force a complete reversal of policy by the Federal Reserve, rebuilding the FI pillar all over again. This could have even greater impacts on PI than in the past due to recency bias (i.e., the mentality “we just had inflation, now the Fed is going to cause it again”).

Given the current inflationary environment, the financial and economic forecast has the *potential* to be dire. As Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, said at a conference on 6/1, “[an economic] hurricane is right out there, down the road, and it’s coming our way. We just don’t know if it’s a minor one or Superstorm Sandy.” The ultimate decider, in my opinion, is going to be the labor market. If hiring freezes, layoffs, job cuts, etc. begin working their way through the broader economy, the economic “pressures” could line up just right for this to be a true economic superstorm toppling all 3 pillars at once (forgive my hurricane naivete). Only time will tell, stay tuned.

How does government spending impact inflation? How does stopping or slowing down production of good and services impact inflation? What leads to hyper inflation, what would it take for hyper inflation to take place in America?

Thanks for the comment! While government spending’s impact is not always a contributing factor to inflation, the response to COVID’s economic impacts certainly were. If we take this to the extreme, imagine the US government sends every person $1M tomorrow. This wouldn’t magically make everyone rich, it would simply increase the price of everything dramatically, thus inflation.

Stopping or slowly production of goods reduces overall supply. Assuming the level of demand remains constant, this ultimately leads to an increase in prices. The same number of people trying to by a smaller number of goods = inflation. We have seen this first-hand across many goods throughout the last 2 years.

Hyperinflation is typically defined as sustained increases in prices in excess of 50%. This generally occurs in an out-of-control manner and can be caused from an excessive increase in money supply (i.e. the government or central bank issuing large amounts of currency) or a complete loss in confidence of an economic system (i.e. the currency becomes worthless because there’s no economy to back it up). It is unlikely hyperinflation will occur in the US and is more characteristic of emerging market economies with very heavy foreign debt burdens.